Introduction

In this article, I will share what I learned about .NET memory management by troubleshooting a memory leak issue for a .NET service running in a real production environment. After reading this post, you can understand more about the following items:

.NET Memory Managementand.NET Garbage Collection- Diagnose memory usage with

WinDbg

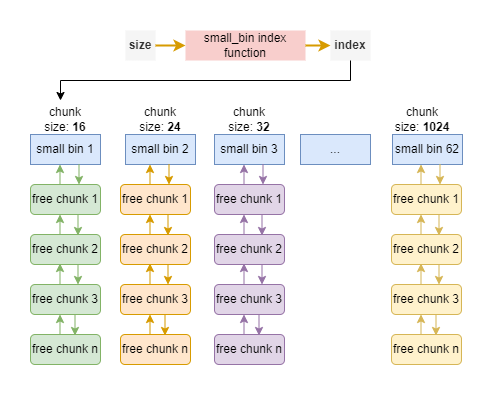

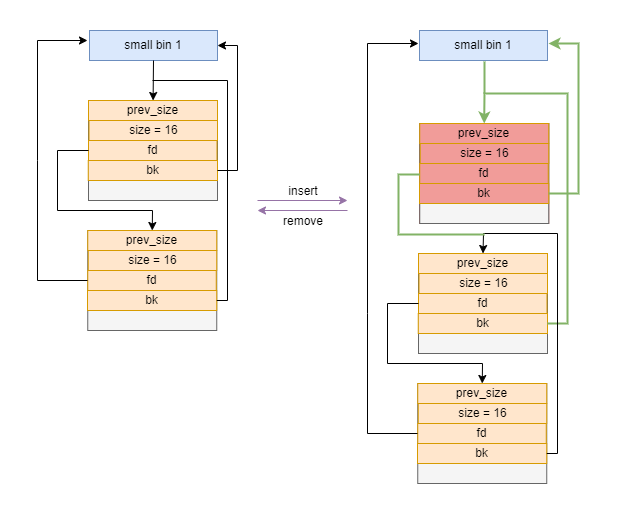

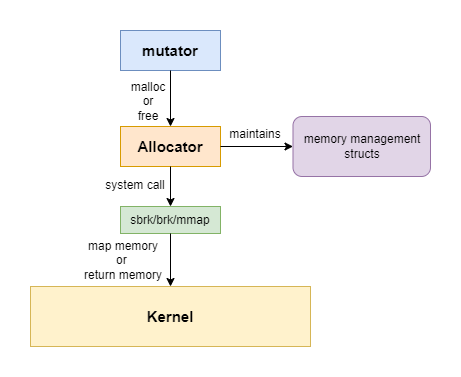

Previously I once published articles about memory allocation of native applications written in C on Linux systems. I highly recommend you read both articles and compare what’s the difference, this can deepen your understanding of memory-related techniques.

Background

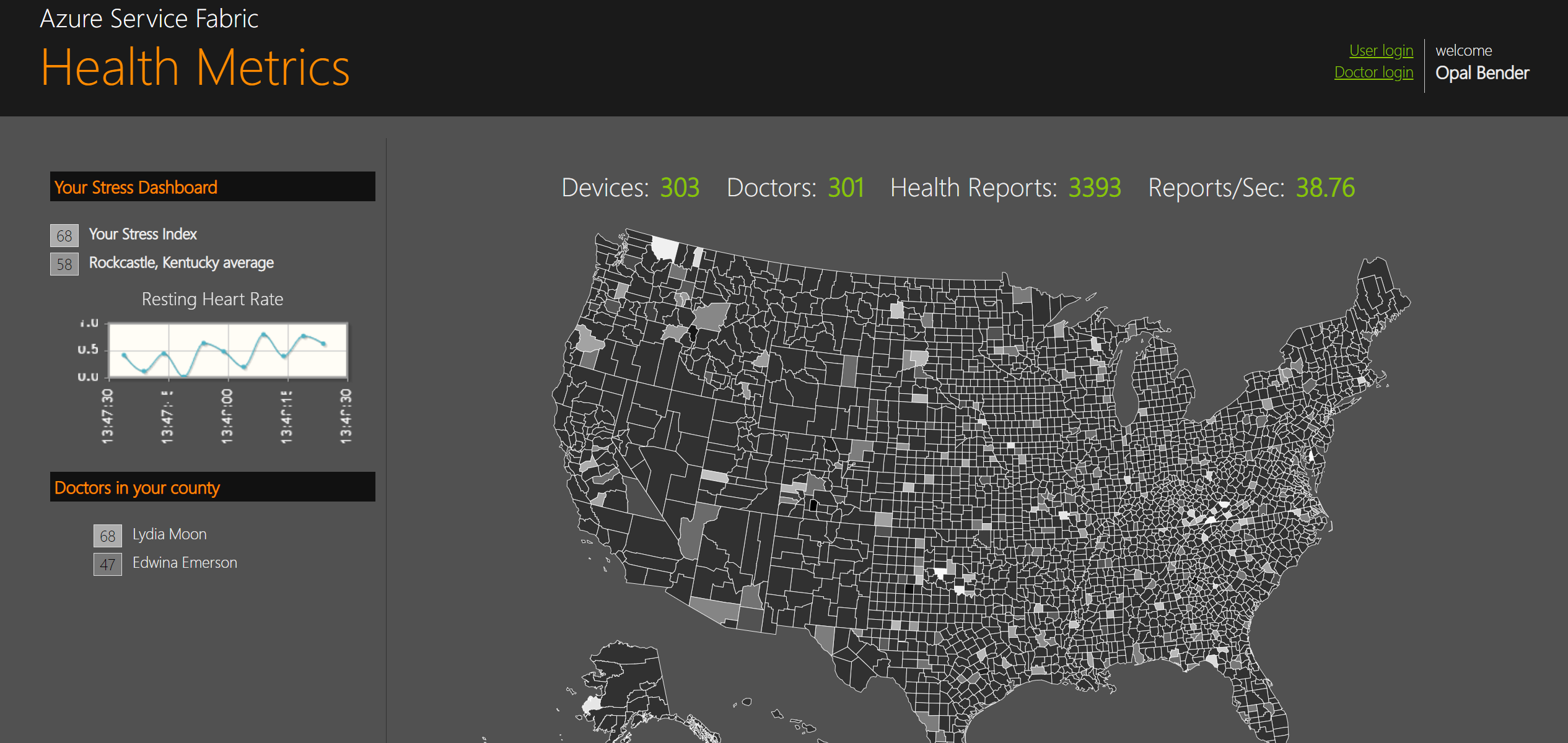

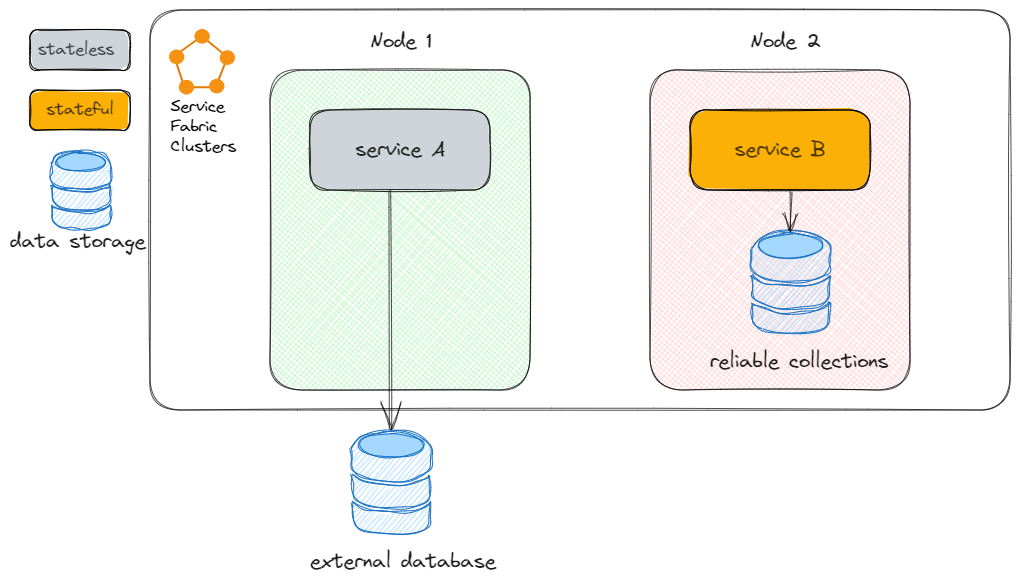

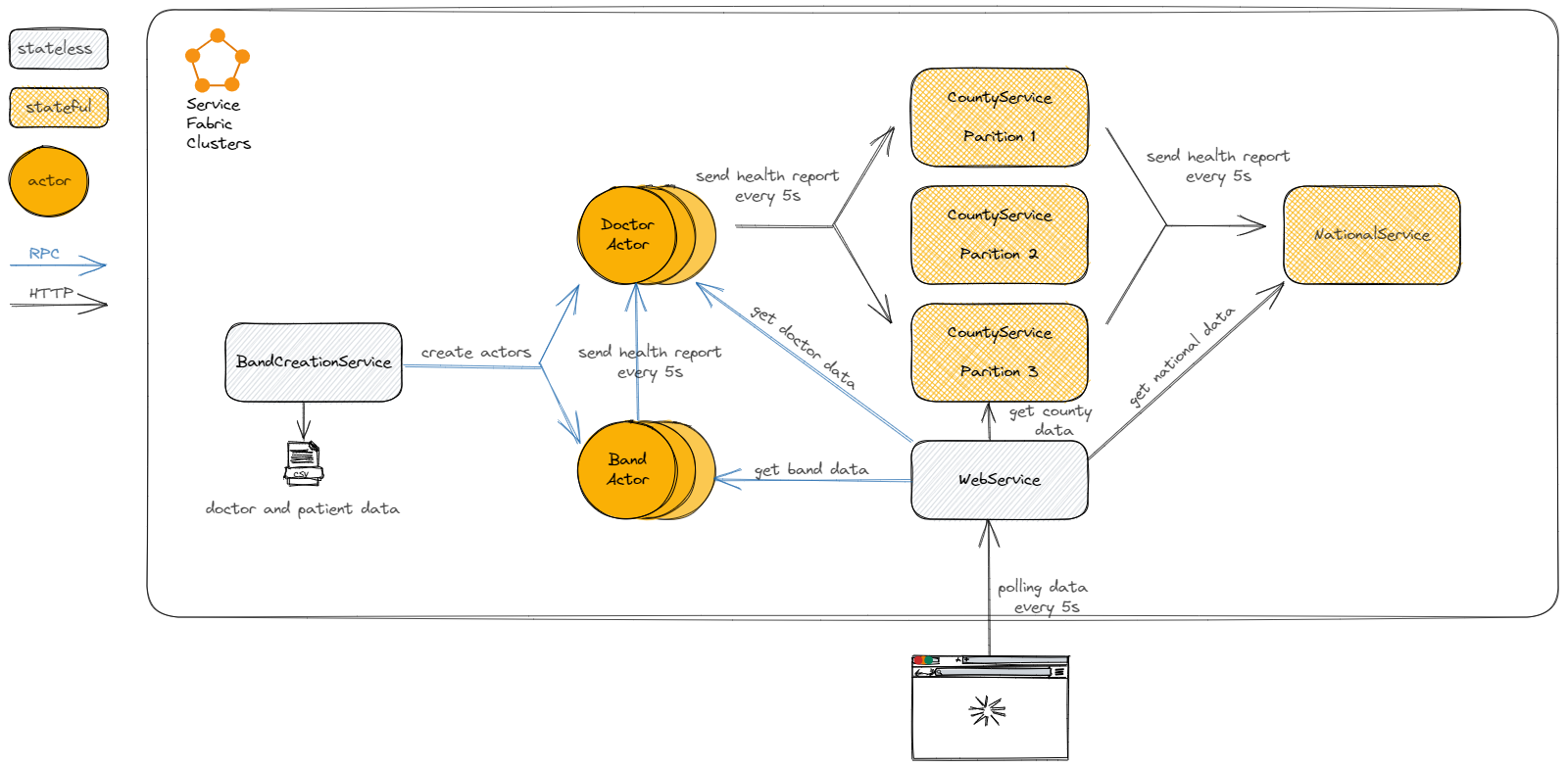

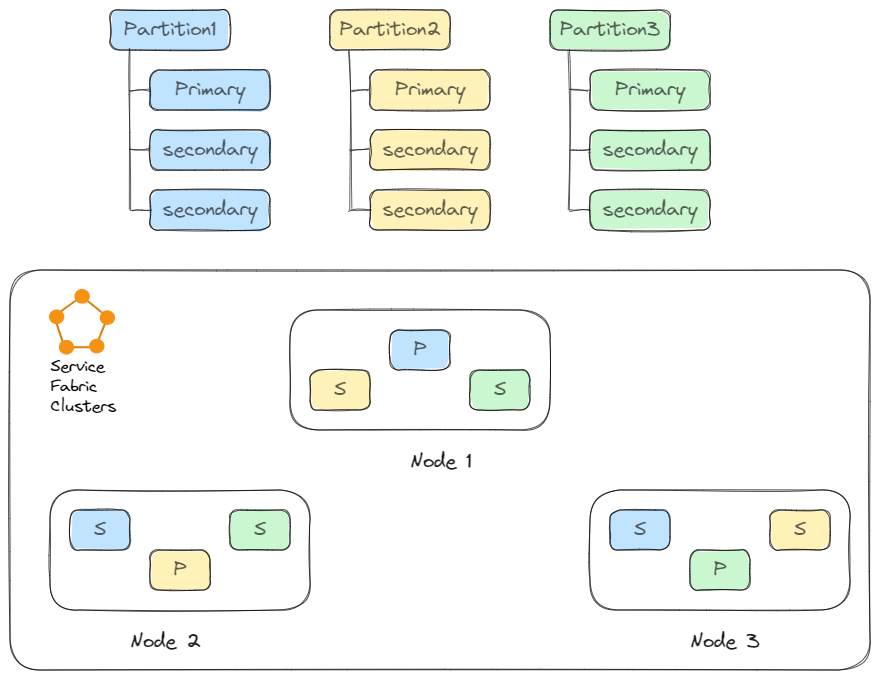

Firstly, let me explain the background: the problematic .NET service is running on the Azure Service Fabric, which consists of a cluster of Windows Server. If you are not familiar with Service Fabric, please refer to my previous article, which explains how to develop microservices based on it. The problem is that the memory usage of this .NET service reaches roughly 1.5GB, which is 4 times higher than the average usage. Generally speaking, on the cloud more resource usage means higher cost. Next, let’s diagnose what is happening here. But before we roll up our sleeves to debug this issue, let’s first review how .NET memory works at a theoretical level.

.NET Memory Management

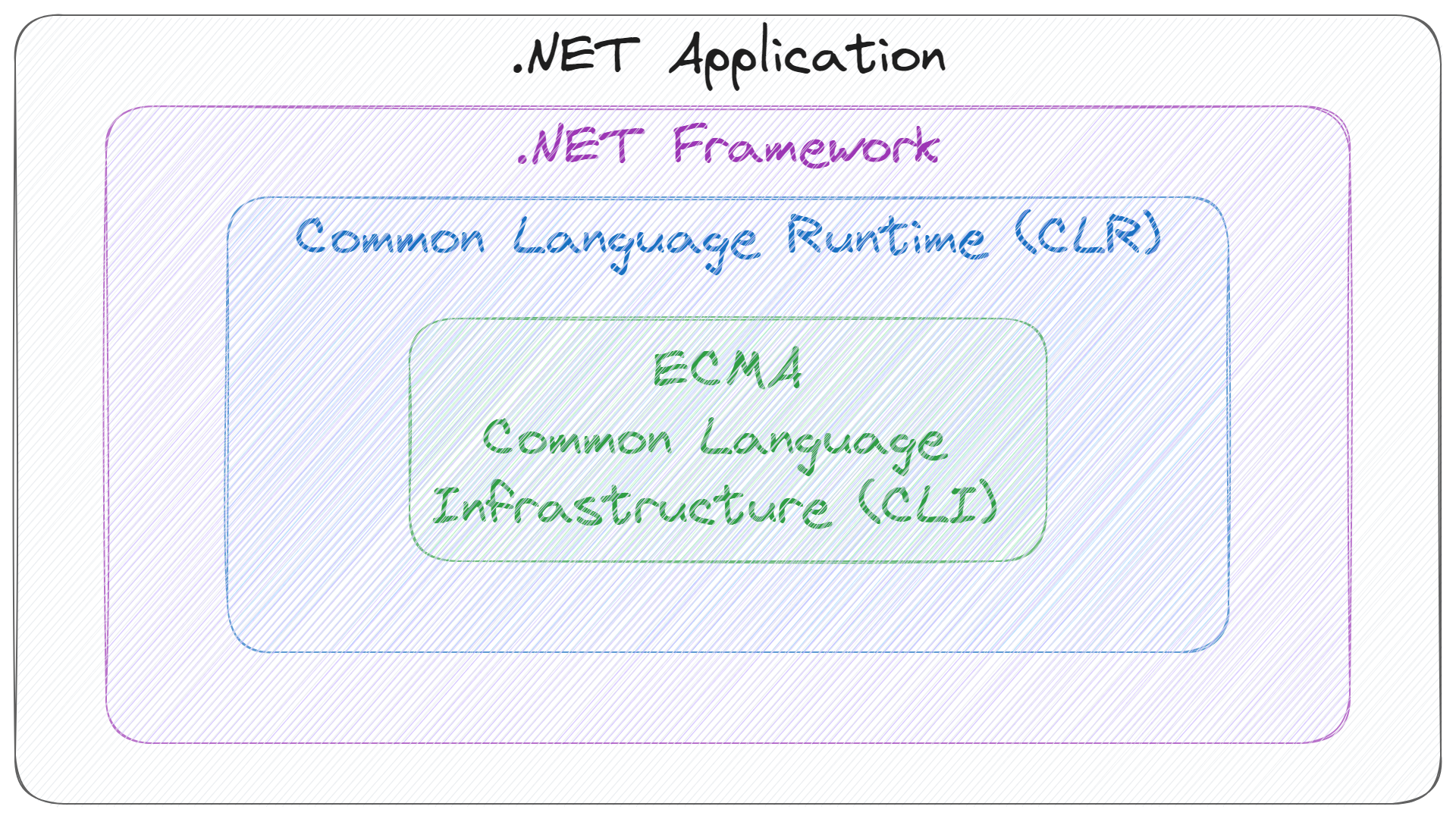

.NET Runtime

Unlike native software written directly to the operating system’s APIs, programs written with .NET are called managed applications because they depend on a runtime and framework that manages many of their vital tasks and ensures a basic safe operating environment. In .NET, runtime refers to the Common Language Runtime(CLR) and the framework is .NET Framework or .NET Core. And the .NET application is built on top of them.

CLR works as a virtual execution engine for .NET applications, and it is a very complex topic that is out of the scope of this article, so we can’t dive into the details. But one of the crucial functionalities it provides is just: memory management.

.NET GC

When you’re working on system programming with C or C++, you need to manage the memory by calling standard library’s APIs like malloc and free to allocate and release the memory. But on the .NET framework, your life will be easier since the .NET memory manager does this task for you. When the program creates a new object, the memory manager will allocate the memory for you. Easy, right? But that’s only a trivial part of the memory manager, the complicated task is how and when the memory manager can decide to collect the memory. Because of this, the .NET memory manager has another name: .NET Garbage Collector.

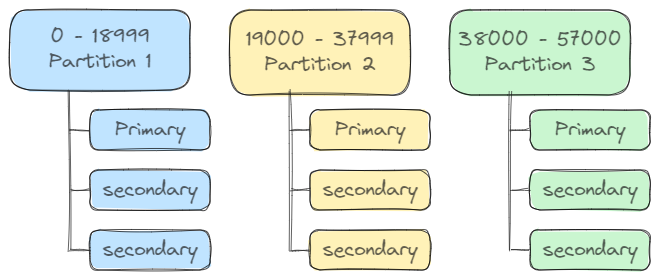

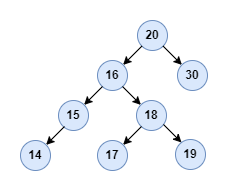

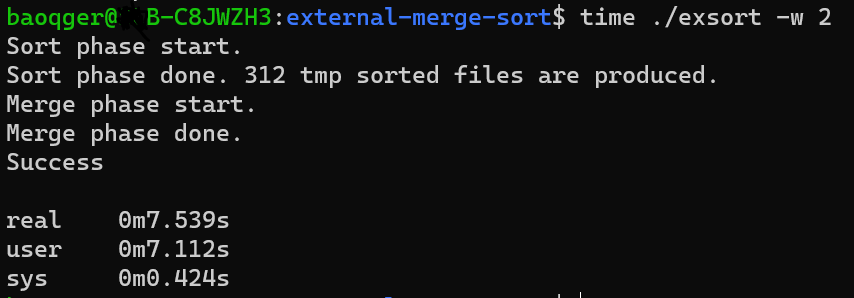

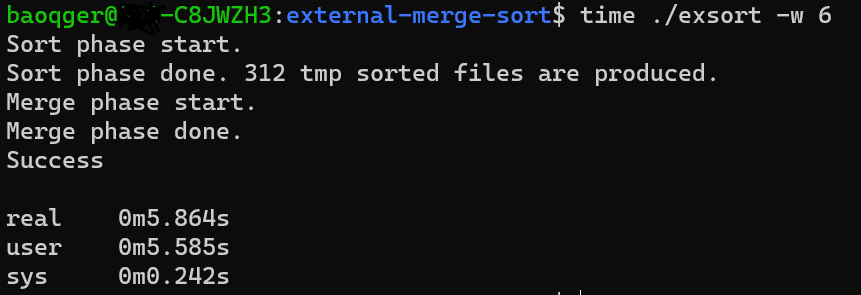

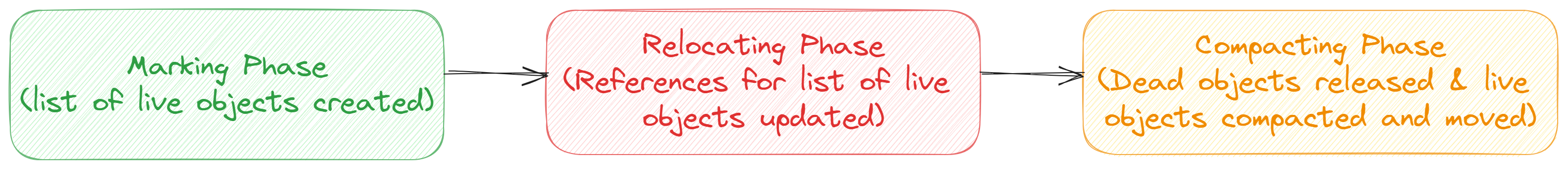

The .NET GC uses two Win32 functions VirtualAlloc and VirtualFree for allocating a segment of memory and releasing segments back to the operating system respectively. The entire process can be divided into the following three phases:

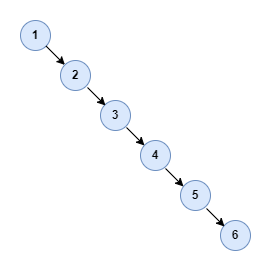

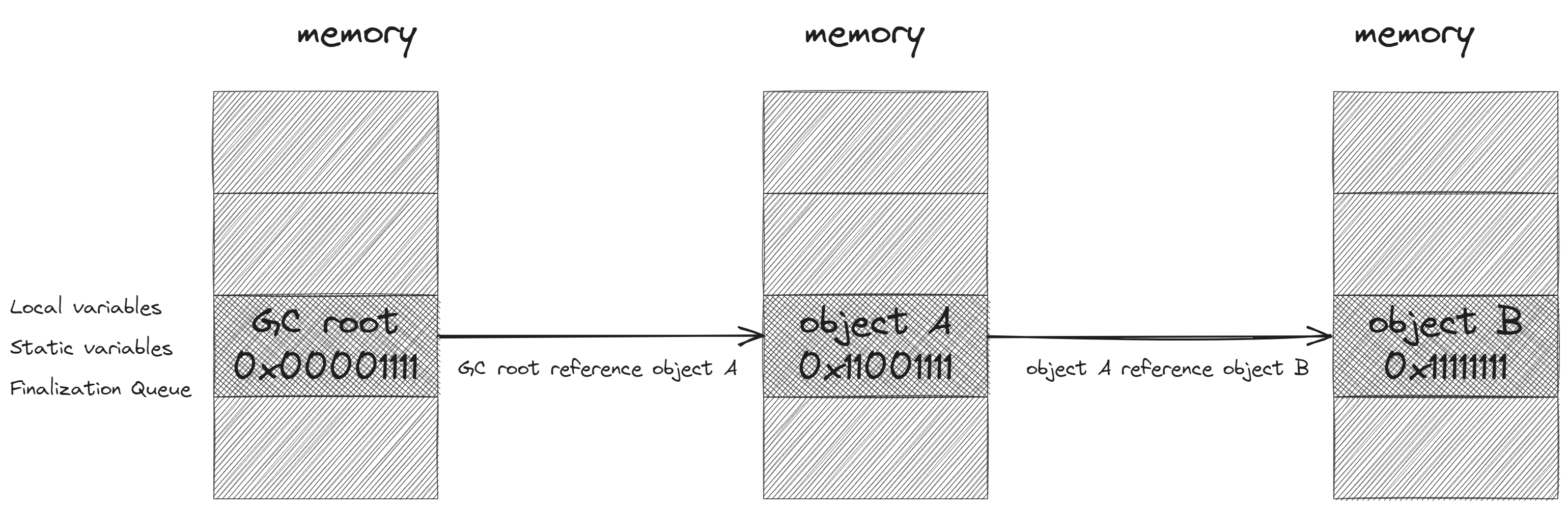

- Marking Phase: A list of

liveobjects is created during the marking phase. This is done by starting from a set of references called theGC roots. GC marks these root objects asliveand then looks at any object that they reference and marks these as beinglivetoo. And the GC continues the search iteratively. This process is also calledreachability analysis. All of the objects that are not on the reachable list are potentially released from the memory.

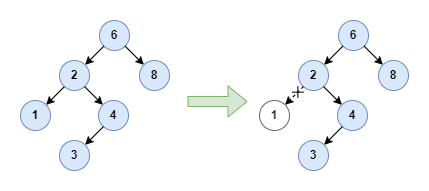

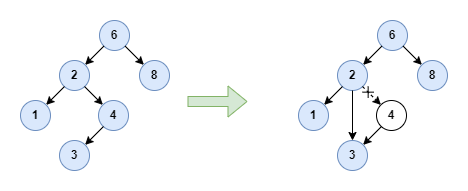

Relocating Phase: The references of all the reachable objects are updated so that they point to the new location. The purpose of the relocating phase is to optimize memory usage by compacting the live objects closer together. This helps reduce

memory fragmentationand improves memory allocation efficiency.Compacting Phase: The memory space occupied by the dead objects is released and the live objects are moved to the new location.

GC algorithm is a complex topic, the above description only touches the surface of it. You can explore more by yourself. In the following sections, I will add extra information when necessary.

WinDbg

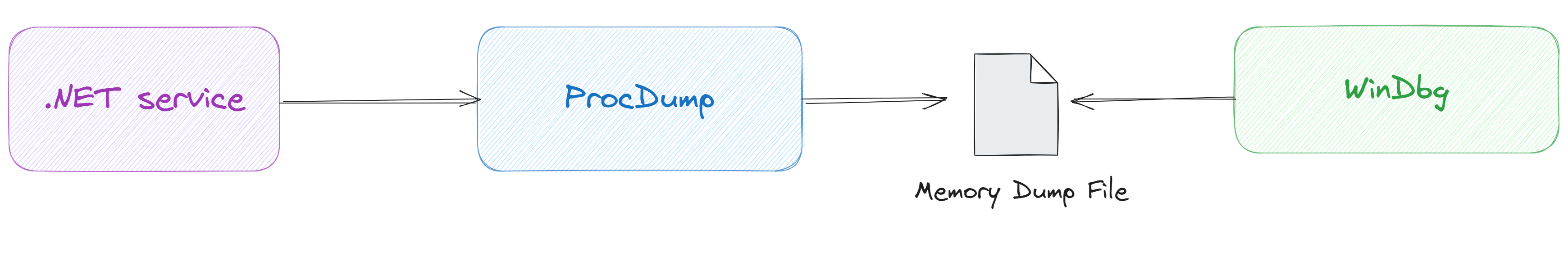

To diagnose .NET applications’ memory issues, there are many modern tools, like dotMemory. But in this article, I will show you a low-level tool: WinDbg. WinDbg is a multipurpose debugger for the Windows OS, which can be used to debug both user mode and kernel mode. Originally WinDbg was used to debug the native applications, but WinDbg allows the loading of extensions which can augment the debugger’s supported commands. For example, to debug .NET applications running on CLR, we need the SOS extension.

Now that we have a powerful debugger in hand, the next question is how to use it. Generally speaking, you can attach the debugger to the problematic service, but since the target service is running in the production environment, we can’t do that easily. So we need to troubleshoot this issue in the offline style as follows:

We need to use ProcDump to dump the memory information into a file, called dump file. Then use WinDbg to analyze the dump file. I will not cover the usage of ProcDump in this article and leave it to you.

Next, let’s play with the dump file, all right? Let’s go!

Diagnose the memory leak

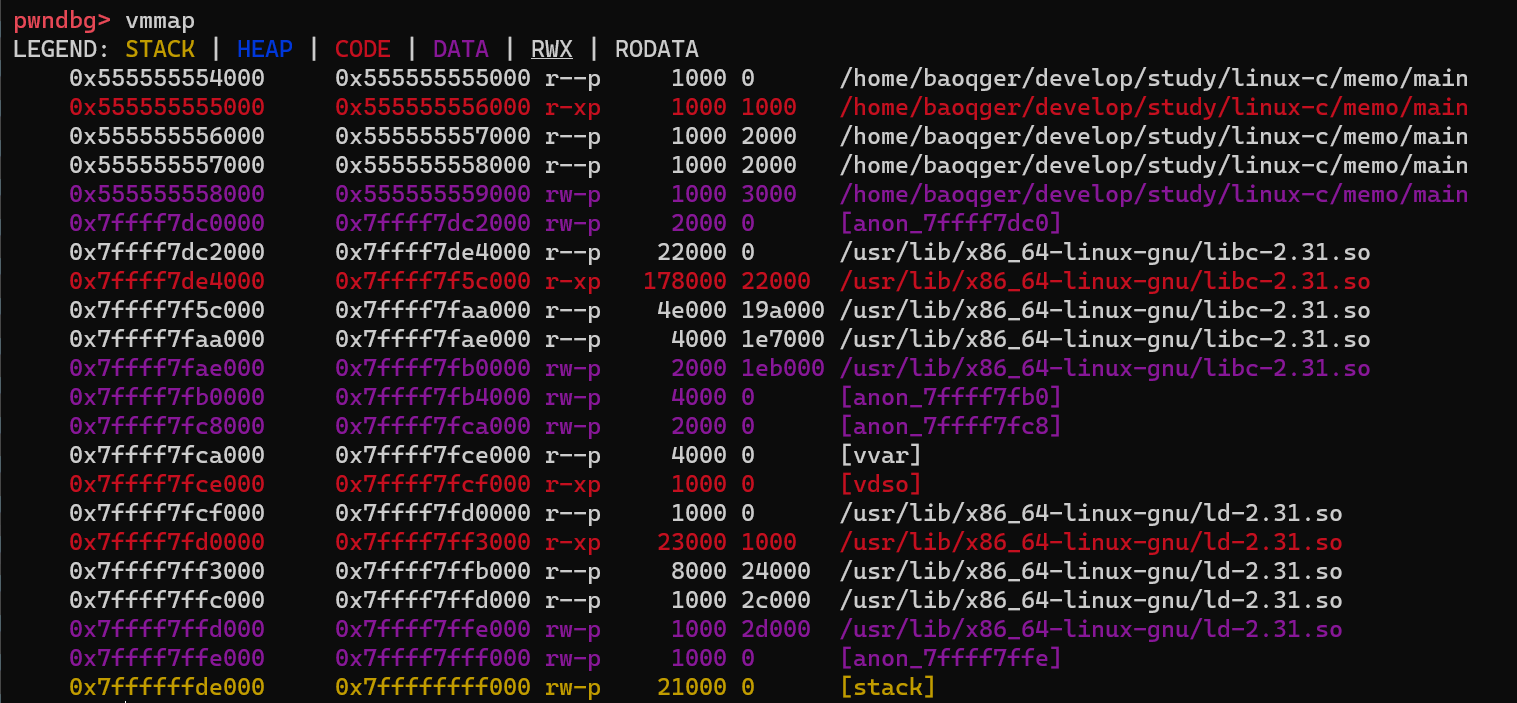

First, let’s use the WinDbg !address extension to display information about the memory that the target process or target computer uses as follows:

1 | 0:000> !address -summary |

Let’s examine the output, which provides so much information!

The first section shows the memory Usage Summary:

- Free: is the entire

virtual memorythat can potentially be claimed from the operating system. This may includeswap space, not only physical RAM. For a 64-bit process, the virtual memory is128TB. - Heap: what you see as

Heapis the memory that was allocated through theWindows Heap Manager, we generally call it thenative heap. - Unknown: any other heap managers will implement their own memory management. Basically, they all work similarly: they get large blocks of memory from

VirtualAllocand then try to do a better management of the small block within that large block. Since WinDbg doesn’t know any of these memory managers, that memory is declared asUnknown. It includes but is not limited to the managed heap of.NET. In my case, the value is3.98GBwhich is much bigger than the1.5GBmemory usage reported by the monitor tool. I will explain why it goes like this in the following sections. - Image: is the memory space allocated for the binary assemblies.

- Stack: is straightforward. If you don’t know, please refer to my previous article.

The second section shows the usage by memory Type: MEM_PRIVATE, MEM_IMAGE and MEM_MAPPED. MEM_PRIVATE is private to one process and MEM_IMAGE and MEM_MAPPED can be shared among multiple processes.

The third section shows the usage by memory State.

- MEM_COMMIT: committed memory refers to the portion of the virtual address space that has been allocated and backed by physical memory or the paging file. Committed memory is actively used and accessible by the process. It includes memory regions that have been allocated and are in use, such as code, data, and heap allocations.

- MEM_RESERVE: corresponds to reserved memory. Reserved memory refers to memory that has been reserved in the virtual address space but has not yet been committed. When memory is reserved, the address space is allocated, but physical memory or paging file resources are not immediately allocated. The process reserves the address space to ensure that it will be available when needed. Reserved memory can later be committed to make it usable by the process.

- MEM_FREE: represents free memory. This category includes all memory that has not been reserved or committed.

In my case, the committed memory is 1.528GB, which exactly matches the monitored memory usage. This can perfectly explain the confusing point mentioned about the 3.98GB unknown memory segment. It turns out the majority of these memories are only reserved. So next step is to get the actual committed memory usage for various types. How to achieve that?

Thanks for the powerful address extension, I can do that by adding some filters like this:

1 | !address -f:MEM_COMMIT -c:".echo %1 %3 %5 %7" |

This command will output all the committed memory regions, and for each region prints its base address(%1), region size(%3), state(%5) and type(%7). The output goes as follows:

1 | 0x5f3a0000 0x1000 MEM_COMMIT Image |

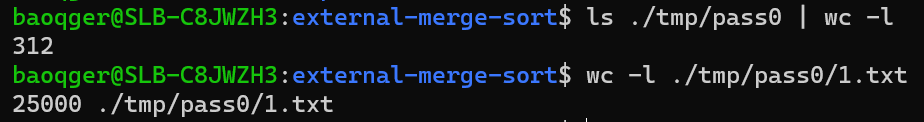

I wrote a simple script to parse the above output and finally got the following result:

1 | Memory by Type: |

Based on this result, you can see the majority comes from the unknown segment. I suspect that the memory leak issue occurs in this problematic service. Various WinDbg commands can diagnose the memory leak problem. And in this specific case, I find the command !finalizequeue is super helpful!

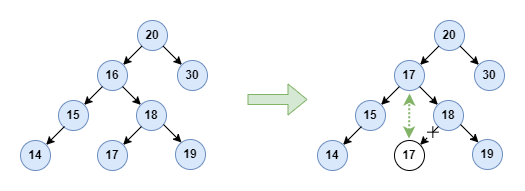

Before I show you the output of the command, let’s examine what the finalizer queue is. In C#, the finalizer(also referred to as destructor) is used to perform any necessary final clean-up when a class instance is being collected by the GC.

1 | class Car |

When your application encapsulates unmanaged resources, such as windows, files and network connections, you should use the finalizer to free those resources.

Objects of classes with finalizers can’t be removed immediately: they instead go to the finalizer queue and are removed from memory once the finalizer has been run.

Based on this, let’s examine the output of command !finalizequeue:

1 | 0:000> !FinalizeQueue |

You can notice that there are 3639 objects of type System.Reflection.Emit.DynamicResolver. As we know, the objects in the finalizer queue can’t be removed until the finalizer runs. This also means that any object they reference and any object referenced by those, and so on has to be kept in memory.

This is the potential reason for the memory leak problem. System.Reflection.Emit is a low-level library used to generate the Microsoft Intermediate Language (MSIL) dynamically, my application does not rely on it. Finally, it turns out the issue is from the Service Fabric SDK and upgrading to new versions can fix it.

Summary

In this article, we examined how .NET GC works and how to diagnose the memory leak issue with WinDbg.