Introduction

In my eyes, compared with developing applications with high-level programming languages, one of the biggest differences for system programming with low-level languages like C and C++, is you have to manage the memory by yourself. So you call APIs like malloc, and free to allocate the memory based on your need and release the memory when the resource is no longer needed. It is not only one of the most frequent causes of bugs in system programming; but also can lead to many security issues.

It’s not difficult to understand the correct usage of APIs like malloc, and free. But have you ever wondered how they work, for example:

- When you call

malloc, does it trigger system calls and delegate the task to the kernel or there are some other mechanisms? - When you call

malloc(10)and try to allocate 10 bytes of heap memory, how many bytes of memory do you get? 10 bytes or more? - When the memory is allocated, where exactly the heap objects are located?

- When you call

free, is the memory directly returned to the kernel?

This article will try to answer these questions.

Note that memory is a super complex topic, so I can’t cover everything about it in one article (In fact, what is covered in this article is very limited). This article will focus on userland memory(heap) allocation.

Process memory management overview

Process virtual memory

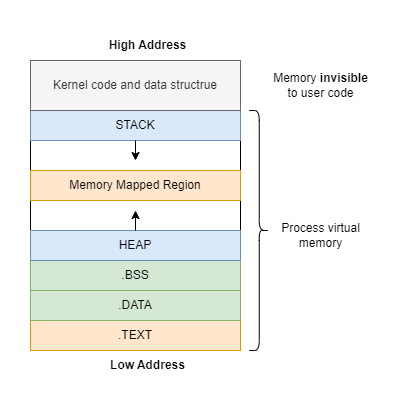

Every time we start a program, a memory area for that program is reserved, and that’s process virtual memory as shown in the following image:

You can note that each process has one invisible memory segment containing kernel codes and data structures. This invisible memory segment is important; since it’s directly related to virtual memory, which is employed by the kernel for memory management. Before we dive into the other different segments, let’s understand virtual memory first.

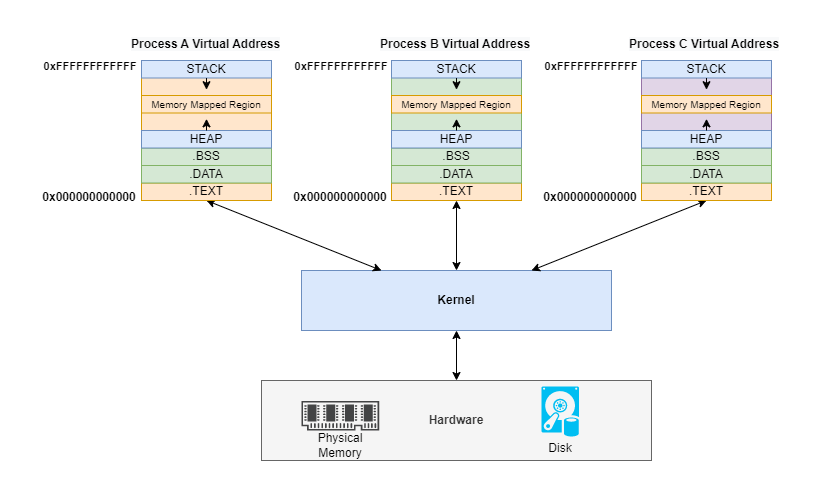

Virtual memory technique

Why do we need virtual memory? Virtual memory is a service provided by the kernel in the form of abstraction. Without virtual memory, applications would need to manage their physical memory space, coordinating with every other process running on the computer. Virtual memory leaves that management to the kernel by creating the maps that allow translation between virtual and physical memory. The kernel creates an illusion that each process occupies the entire physical memory space. We can also realize process isolation based on virtual memory to enhance security.

Virtual memory is out of this article’s scope, if you’re interested, please take a look at the core techniques: paging and swapping.

Static vs Dynamic memory allocation

Next, let’s take a close look at the process memory layout above and understand where they are from. Generally speaking, there are two ways via which memories can be allocated for storing data: static and dynamic. Static memory allocation happens at compile time, while dynamic memory allocation occurs at runtime.

When a program started, the executable file(on the Linux system, it’s called an ELF file) will be loaded into the memory as a Process Image. This ELF file contains the following segments:

- .TEXT: contains the executable part of the program with all the machine codes.

- .DATA: contains

initializedstatic and global variables. - .BSS: is short for

block started by symbolcontainsuninitializedstatic and global variables.

The ELF file will be loaded by the kernel and create a process image. And these static data will be mapped into the corresponding segments of the virtual memory. The ELF loader is also an interesting topic, I will write another article about it in the future. Please keep watching my blog!

The memory-mapped region segment is used for storing the shared libraries.

Finally, stack and heap segments are produced at runtime dynamically, which are used to store and operate on temporary variables that are used during the execution of the program. Previously, I once wrote an article about the stack, please refer to it if you want to know the details.

The only remaining segment we didn’t mention yet is the heap, which is this article’s focus!

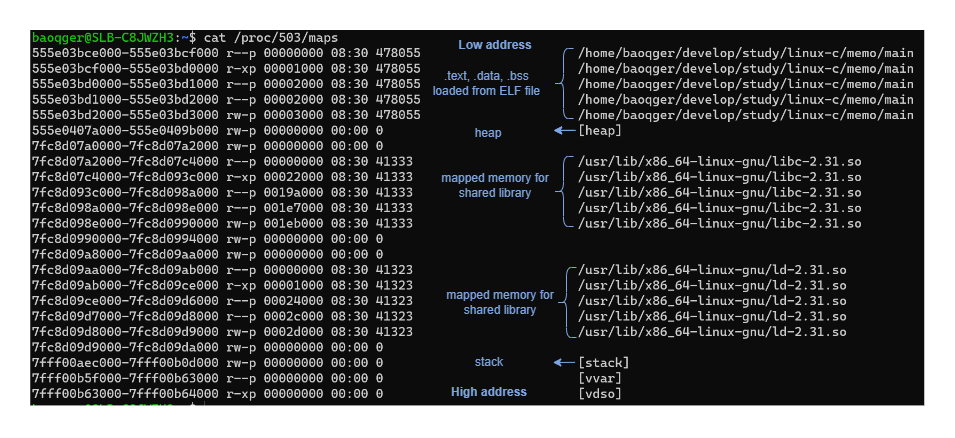

You can check the memory layout of one process by examining this file /proc/{pid}/maps as below:

Note that the above investigation doesn’t consider multiple threads. The memory layout of the process with multi-threads will be more complex, please refer to other online documents.

In this section, we had a rough overview of memory management from top to bottom. Hope you can see the big picture and know where we are. Next, let’s dig into the heap segment and see how it works.